After completing my PhD in Carbohydrate Enzymology at Newcastle University, UK, supervised by Prof. Harry Gilbert, I moved to KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden. For the first couple of years I worked as a post-doc under Prof. Harry Brumer, and it was during this time that my still-ongoing connection to the Wallenberg Wood Science Centre (WWSC) began. After Harry moved to the University of British Columbia in Canada, I worked as a post-doc and then a junior researcher (same basic duties but a more permanent form of employment) under the supervision of Prof Vincent Bulone. In 2017 I started bringing in my own independent funding, and agreed with Vincent that I could spend part of my time on my own projects. Over time, my independent financing increased to the point where I could pay my own salary and (sometimes) those of other people, so I was able to become an independent Researcher (Forskare was my official Swedish title) at KTH, working as a group leader, recruiting my own students and post-docs to work on projects I designed. My position for these years was non-tenured and outside of the faculty track, and entirely financed my own grants. At the same time, as my independence grew, I diversified my activities and started to teach on various courses in the MSc Biotechnology degree programmes at KTH, which are taught in English. After building my skills and academic contributions in research, teaching, academic service, and public outreach, I was assessed and awarded the distinction of Docent in 2020, a process I blogged about at the time, and in 2023 I became a vice-director of the WWSC’s PhD Academy. Finally, in 2024 I was appointed Associate Professor in Cell Wall Biochemistry at the KTH Division of Glycoscience! I applied to this externally advertised tenure-track faculty position and went through a competitive interview process in September 2024, officially starting in my new role in November.

Through the years of working with Harry, Harry, Vincent, and my own group, my research has touched on enzyme discovery, enzyme characterisation, cell wall analysis, some bioprocess design, and microbial pathogenesis in plants and animals. Below, you can read some details about current and recent research projects I’ve worked on. My major interest is soil microorganisms and how they interact with the environment around them. These interactions are important for biogeochemical cycles, soil fertility, and plant health. The enzymes produced by soil microbes can also be valuable biotechnological tools. I run a small research group of students and postdocs at KTH in Stockholm, Sweden, in the Division of Glycoscience. This page describes where our research funding comes from, and I’ll update if and when I secure more support! If you’re a student interested in working on a thesis or diploma project with me, visit my professional webpage for details of how to get in touch. You can learn about the working culture of our labspace in this article. And you can find a full list of my academic publications at this link.

Biocontrol

Biological control is the use of living organisms to control pests and pathogens, instead of using chemical pesticides. This can mean animals are used to control insect populations, or that bacteria are used to kill pathogenic fungi. Picture source.

Exploring the potential for fungal antagonism and cell wall attack by Bacillus subtilis natto. The natto bacterium is used in food production in Japan, but had not been considered for biocontrol, although it lives in the soil and produces enzymes associated with anti-fungal properties. We investigated the biocontrol potential of natto, focussing on whether we could enhance such behaviours by changing culture conditions.

The impact of steroidal glycoalkaloids on the physiology of Phytophthora infestans, the causative agent of potato late blight. Plant breeders and farmers need to know what traits to select for in crop plants that are threatened by disease. The potato has suffered from blight for centuries. We investigated potato compounds called glycoalkaloids to see what effect they had on an especially nasty potato pathogen. Our results could guide potato breeders in selecting for useful traits.

Soil bacteria

I’m fascinated by bacteria that can sense specific carbohydrates (like in plant and fungal cell walls) and respond by producing specific enzymes. A better understanding of the complex microbe-microbe interactions in the soil will help us to better manage the soil microbial ecosystem. Picture source.

Bacteroidetes bacteria in the soil: Glycan acquisition, enzyme secretion, and gliding motility. This book chapter, co-written with my good friend Dr Johan Larsbrink at Chalmers University in Gothenburg, summarised the state of the art on carbohydrate metabolism by soil bacteria in the Bacteroidetes genus, for whom nutrient acquisition is closely genetically tied to carbohydrate sensing and the ability to glide over solid surfaces. The soil Bacteroidetes have been a bit neglected in research in favour of their cousins in the human gut, and here we argue that their are just as interesting and important, and worthy of investigation.

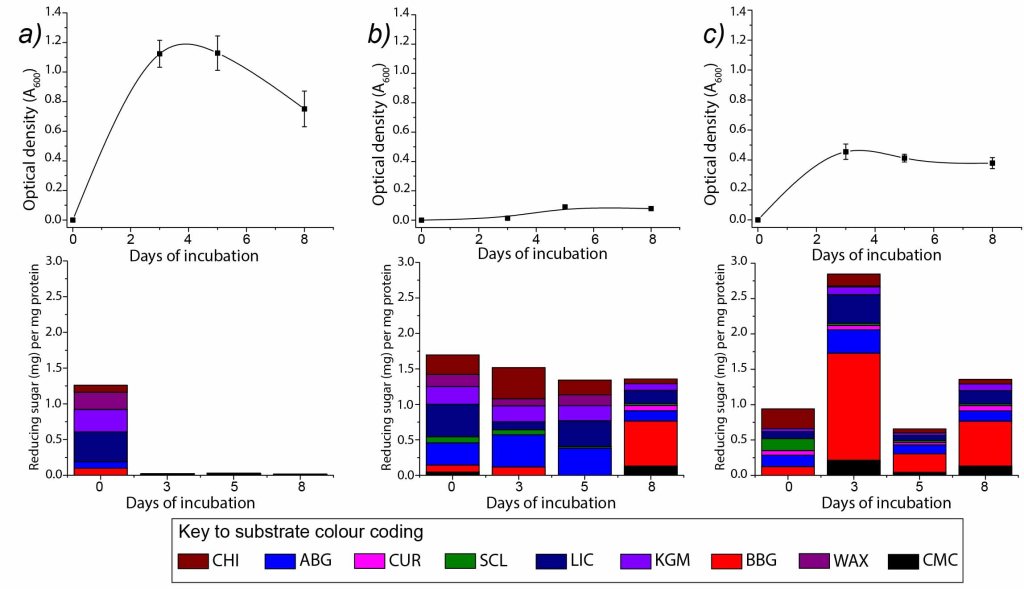

Focussed metabolism of β-glucans by the soil Bacteroidetes Chitinophaga pinensis. We showed that my favourite species, C. pinensis, has a strict preference for using fungal biomass instead of plant biomass as a source of nutrition. This will guide our efforts to characterise enzyme activities, as it gives hints to likely enzyme substrates.

Proteomic insights into mannan degradation and protein secretion by the forest floor bacterium Chitinophaga pinensis. We used a technique called mass spectrometry to help us identify the proteins that C. pinensis secretes when grown in different conditions. This can tell us the actual enzymes involved in different processes, and which combinations of enzymes are produced at the same time.

Enzyme discovery

I characterise enzymes with potential use in biomass deconstruction or modification, often in collaboration with the Wallenberg Wood Science Centre (WWSC). Enzymes can be useful at almost every step of a wood biorefinery, to separate wood components, add new functionalities, or combine them into novel materials. Picture source.

Lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs) mediated production of ultra-fine cellulose nanofibres from delignified softwood fibres. Nanocellulose is an amazing material – it has the strength of steel if you prepare it correctly, and it can be made from waste wood or paper! Conventional process for making nanocellulose use a lot of nasty chemicals, which we should move away from. This study showed how a single enzyme can be used to make nanocellulose from softwood in mild, energy-efficient reaction conditions.

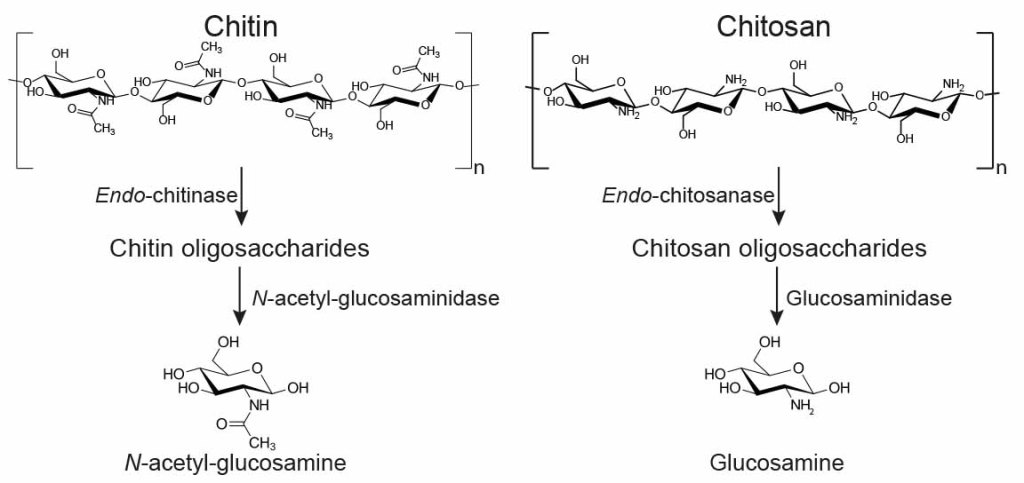

Production of functionalised chitins assisted by fungal lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase. Chitin is a natural polymer found in shellfish and fungi that has great material properties and even bioactive properties, like inhibiting bacterial growth. We described a new enzyme that lets us make functional chitin with nanoscale dimensions while avoiding using the nasty chemicals that are typically required.

A GH115 α-glucuronidase from Schizophyllum commune contributes to the synergistic enzymatic deconstruction of softwood glucuronoarabinoxylan. Industrial use of biomass for the production of fuel, materials, or chemicals has to begin with separation of the biomass components. With waste from the forestry and agricultural sectors, this is tricky, because the biomass is so complex. We designed an enzyme cocktail allowing full deconstruction of one of the most complex carbohydrates in softwood.

A discrete genetic locus confers xyloglucan metabolism in select human gut Bacteroidetes. This was a very cool study, and my first experience of publishing in a properly famous journal (Nature). The work attracted a lot of press attention when it was published. We investigated the enzymology of a human gut bacterium, and were the first to describe a complete deconstruction pathway for one polysaccharide in the gut. We focussed on xyloglucan, found in lettuce, tomato, and many other fruits and veg.

Cell walls

Cell walls from plants and fungi are the substrates for my bacterial enzymes, and it’s important to know what they look like and how they are made. We’ve used various methods to understand cell wall structure in different organisms. Picture source.

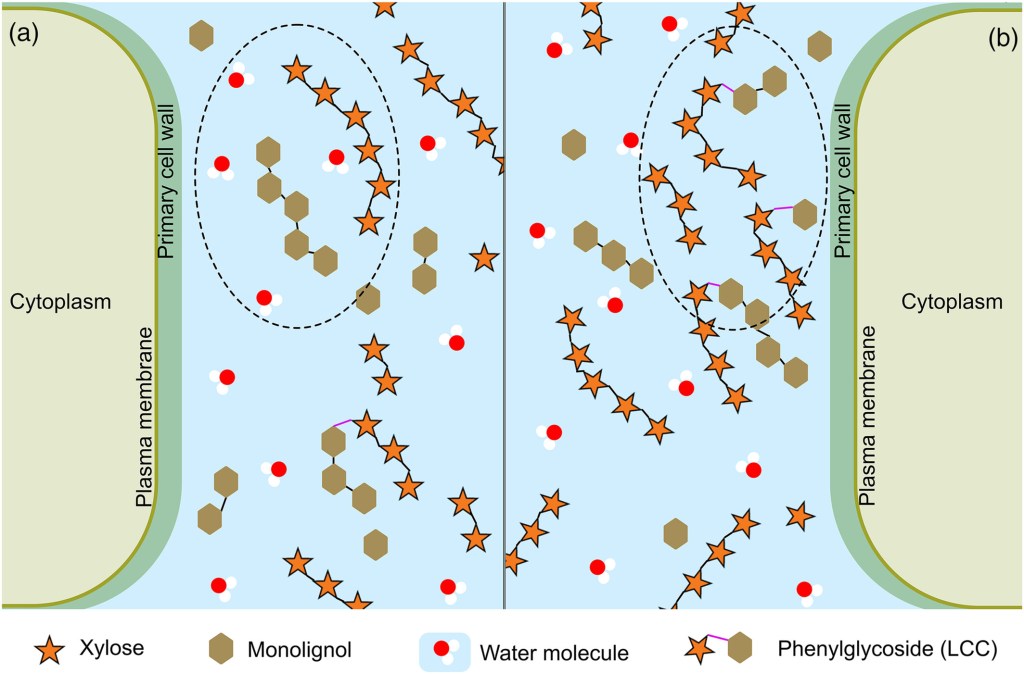

The impact of xylan on the biosynthesis and structure of extracellular lignin produced by a Norway spruce tissue culture. Lignin is a load-bearing and strength-conferring component in plant cell walls, often considered problematic in biorefinery settings, but with tremendous useful properties of its own. To help inform the design of processes that can extract lignin without damaging it, we aimed to better understand its native structure and interaction with other wall components, here using an interesting tissue culture system.

Analysis of a cellulose synthase catalytic subunit from the oomycete pathogen of crops Phytophthora capsici. Understanding cell wall biosynthesis in plant pathogens might allow us to design growth inhibitors that are highly specific, leading to less risk of resistance developing or of the suppression of beneficial microbes. Here, we investigated cellulose biosynthesis in a pathogen of pepper crops.

Spatially resolved transcriptome profiling in model plant species. Spatial transcriptomics is an incredibly powerful technique, providing finely resolved spatial data on gene expression in intact tissues. The method was pioneered in human tissue for medical research, but here we showed that it can be equally well applied to plant tissue – you just need a more elaborate protocol for removing the cell wall without damaging the RNA!

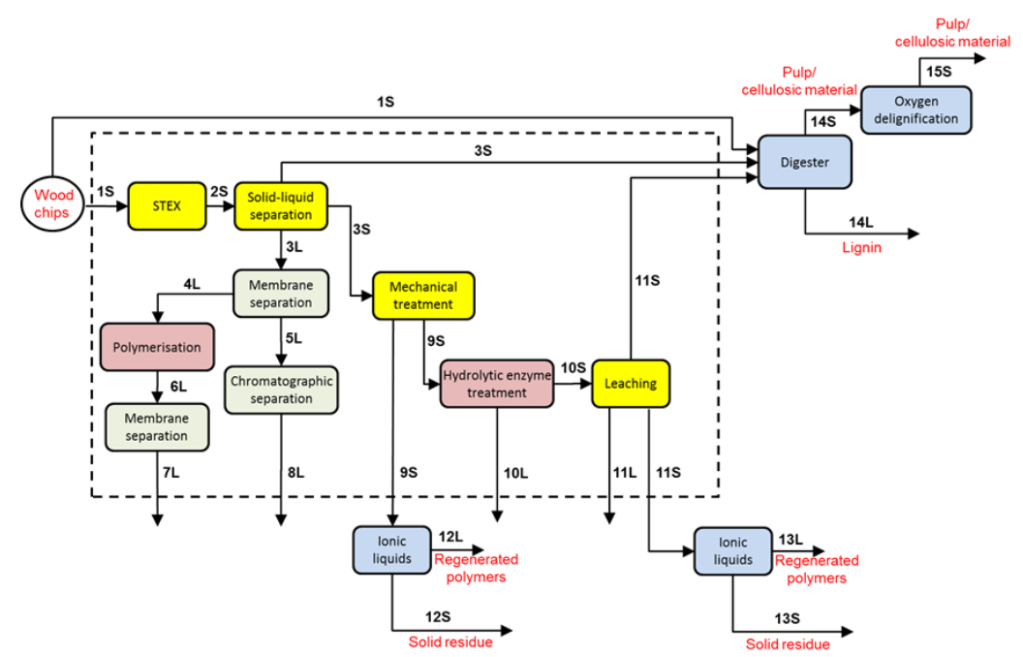

Biorefinery

The biorefinery concept states that we should productive use for all components of the biomass that we use in e.g. food, fuel, and materials manufacture. This often means finding new ways to fractionate materials like forestry or agricultural waste, to preserve the value in each component. Picture source.

Non-targeted discovery of high-value bio-products in Nicotiana glauca L: a potential renewable plant feedstock. As part of an EU project called MultiBioPro, I helped characterise the carbohydrate components of Nicotiana glauca, proposed as a new under-exploited renewable biorefinery feedstock.

Impact of Extraction Method on the Structure of Lignin from Ball-Milled Hardwood. Wood components like lignin are damaged or modified during typical fractionation processes like pulping. This causes them to lose important properties and reduces their overall value. New extraction methods like those explored in this paper are needed so we can re-design biorefinery processes to avoid losing valuable compounds.

Structure-property relationship of native-like lignin nanoparticles from softwood and hardwood. And when we extract lignin in a relatively intact form, we are able to use it to create materials with interesting properties and potential application in encapsulation technologies.